A very long time ago — and by that I mean a couple of years before the pandemic — I was in a record store in downtown Austin. I was picking up some music on compact disc (yes, I know — on brand for a member of Generation X), and the guy ringing me up noted one of the artists I had picked out — a jazz titan of a drummer and bandleader. “Art Blakey,” he said, and then added “Man, if you could hook up to a person like he was a generator, this guy could power an entire city.” Just like that, in only a few words he captured the essence of this artist and made a brief but unmistakable meeting of the minds with me.

Joseph Campbell once told Bill Moyers, “I don’t believe in being interested in a thing because it is said to be important. I believe in being caught by it.” This description perfectly captures what happened to me with jazz back in 1998. That was the year that I found an album recorded in 1979 by the prolific saxophonist Sonny Rollins. I can still remember haunting the Record Exchange at 5th and South during that year, sensing that there was something in this genre for me — despite the fact that I came to it without musical training.

A friend’s father was a jazz drummer, and that was my earliest real exposure. The album she played for me (featuring her dad) was saxophonist Billy Harper’s Destiny is Yours, and it was an incredible tableau of music that struck me as though it could play as a soundtrack for New York City and all of the world’s biggest cities. It was stately and philosophical but also funky. I bookmarked the sound, knowing that I wasn’t completely at home with it yet but that something had been started. In the next year, I followed up on Donald Fagen and Walter Becker’s homages to jazz offered on their recordings as Steely Dan when I picked up a best of Charlie Parker collection and a disc of some of Duke Ellington’s work. One of Duke’s tracks was “Going Up,” featuring a flute performance that lived up to the title. I bought a John Coltrane disc from his final years on Earth, but I wasn’t ready for that music — yet.

I remember the feeling 25 years ago of going into 1999 with a feeling that from then on, I would always have something new in my back pocket: my latest discovery in jazz. In ’99 I was exploring the vocal mastery of Ella Fitzgerald and the guitar prowess of Wes Montgomery. I remember asking my father about Wes, and he looked at me and smiled and said, “Octaves!” He was smiling because the style of playing the same note high and low at the same time is almost like a gimmick, but Wes loved it and made that love contagious with his play. The Incredible Jazz Guitar of his was probably the first jazz album I found that wasn’t predicated on horns or piano as the centerpiece instrument. After being totally captured by his thumbed strings in that small group session, I came across the Verve Master Edition of his disc Movin’ Wes from 1964. It’s a big band album that focuses on swinging, short, sugar highs of sound via movie music and bossa novas. My favorite is the old standard “People,” with Wes delivering a schmaltzy and gorgeous guitar solo that always makes me wish I could have listened to it with my grandfather Bud.

Before the turn of the 21st century, I had the chance to catch a few of the (then) still living and practicing masters perform in concert. On a hot summer night in ’98, I saw the iconic trumpeter/composer Freddie Hubbard (especially known for 1970’s outstanding Red Clay) perform in a fly by night cabaret in a place once called Newmarket in Olde City Philadelphia. Later that same year, I walked the rainy streets of Philly to a venue called The Painted Bride and saw the great saxophonist Sam Rivers. What this group played was wild to me — it sounded avant-garde. I remember that Rivers announced that one composition was called “Ripples!” as he made a flourishing gesture with his hand. Then he took me off guard at the end, playing an r&b rhythm and just riffing on it and calling out the band members and chatting occasionally to the audience.

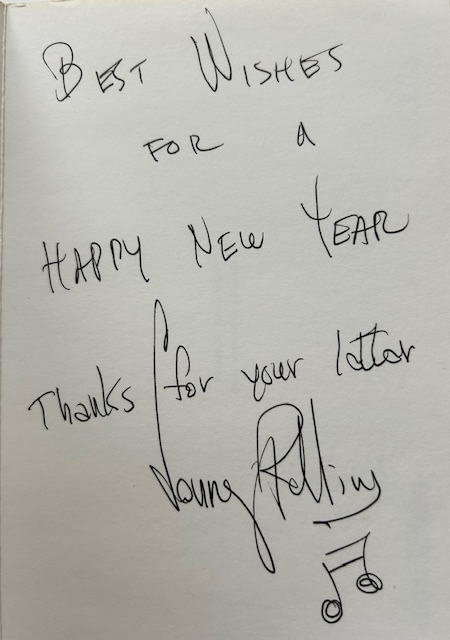

The keystone figure of my jazz concert-going over a decade of my life was the aforementioned Theodore Walter “Sonny” Rollins. Although I never met Sonny in person, I saw him perform five times, and he replied to a letter I once wrote him with a beautiful hand-signed card. His rich tenor sound was almost cavernous at times but always flowing with ideas. I didn’t have a driver’s license in 1998, but I had two tickets to see Sonny for the first time at Pennsylvania’s Keswick Theater, so my cousin Steve supplied the transportation and made use of that second ticket. In 2000, I took my mom and George to see Sonny on the University of Pennsylvania’s campus, and they didn’t need to be jazz fanatics to appreciate what he could do with his horn. In 2007, I took a girlfriend named Meredith to see him at the Kimmel Center — and I’ll simply say that Sonny didn’t mess things up for me.

During those first voracious years of listening, so many things grabbed my attention. I learned how Charlie “Yardbird” Parker and his alto sax revolutionized jazz during the World War II years. In 1949-50 Parker recorded a double album full of standards backed by strings and the drum mastery of Buddy Rich as a kind of elevated platform for the genre and his own innovations. A decade later, tenor saxophonist Stan Getz picked up this torch and produced 1961’s Focus, featuring an amazing 8-minute improvisation of a certain Alice in Wonderland theme called “I’m Late, I’m Late” — with drummer Roy Hanes’s invigorating rhythms and a philharmonic string section. I followed my father’s advice and listened to the electric, bluesy magic of Cannonball Adderley’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy” from 1966 and later found a track I remembered from the radio when I was little: “Birdland,” an electric jazz-rock blend and an homage to a famous New York club named after Parker by the band Weather Report. The tracks on their album Heavy Weather became the soundtrack for science fiction books that I was reading that year including the novelization of 2001: A Space Odyssey and Niven and Pournelle’s futuristic page-turner Oath of Fealty.

In 2000 I couldn’t help but enjoy Ken Burns’s 18-hour documentary Jazz. He and his team provided a comprehensive and justified focus on the lifetimes of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong and an examination of the racial dynamics and injustices of U.S. history as they pertained to this art. Even so, Burns greatly truncated everything that happened after about 1961, which fed into the idea that the music stopped or died by the 1970s. The album that I kept thinking of that he left out was a 1975 Atlantic Records dual release called Changes One and Changes Two by the bassist and fiery bandleader named Charles Mingus. Maybe it was Mingus’s intense temperament that gave birth to Changes, in which he titled the first track “Remember Rockefeller at Attica” in a statement of political protest. If you give it a listen, that track is somehow both angry and artfully swinging. In “Sue’s Changes,” I found a recording that rewrote what music was capable of doing. I didn’t think music could be this attractive, revelatory, and off-putting all at once, but that composition, which was written about Mingus’s wife, mixes pure creativity with a fiery kind of journalism for a full 17 minutes.

As I sat with the music and found the works that really moved me, I began to see the relationships that were at the heart of this music. Julian “Cannonball” Adderley and his brother Nat welcomed the Austrian-born Josef Zawinul to play piano and compose in their groups for 10 years of brilliant partnership and exploration. If you want to get a sense of how creative and catchy Zawinul could be (and how good of an ear Cannonball had), just listen to “Scotch and Water” by the quintet in 1961. This kind of union forged in the development of great jazz could be seen in cases such as Duke Ellington’s musical commitment to Billy Strayhorn as well as the interactions and expeditions of Miles Davis with Gil Evans. Like Adderley, John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie found his own piano genius collaborator from abroad: the incomparable Lalo Schifrin, who hailed from Argentina. Schifrin would go on to create some of the most memorable original soundtracks, including those of T.V. series Mission Impossible and films Cool Hand Luke, Enter the Dragon, and jazz devotee Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry pictures among many others. Going back to the early 1960s and listening to Schifrin’s work with Diz underscores the paradoxical combination of showmanship and discipline found in jazz. In most of these pairings and so many others in the genre, ethnicity and nationality didn’t matter — or if they did matter, these elements enhanced through respect and investment the quality of the resulting repertoire. In 2008 Willie Nelson and jazz great Wynton Marsalis produced a collaboration in this same spirit of meeting on common ground called Two Men with the Blues. These instances of musical co-piloting remain one of the most powerful attractions of jazz for me.

In 2003 I went to the Philadelphia Art Museum to see and hear the music of the maestro Kenny Barron and his trio. The sparse crowd was a bit of a disservice to the quality of the music, but it gave me the opportunity to sit right in the front row and take in the sound thoroughly. Kenny performed contemporary jazz standards such as James Williams’s “Alter Ego” and his own originals, and that concert completely raised the bar for me on how personal and beautiful music could be. After the concert, the thin crowd was once again a benefit as I had the chance to say hello to drummer Ben Riley, who had played in Rollins’s band back in (once again) 1961, appearing on the milestone recording The Bridge. Afterward, I even had the chance to introduce myself to Kenny and to convey a greeting from an old friend of his who was a coworker of mine. These small moments of connection, however brief, underscored for me the idea that although jazz had long ago become a path less traveled, the music spoke to me personally and maintained persistent relationships with almost every aspect of life.

Jazz lends itself quite well to the visual side of things, for example, so it’s appropriate that some of the most innovative film directors have used jazz in the manner of a key supporting cast member in their works. Otto Preminger enlisted Ellington to score the 1959 film Anatomy of a Murder. There is something so satisfying about watching Jimmy Stewart playing up his “old country lawyer” persona in the film as Duke’s distinctive band and arrangements set the mood and accompany the action. At one point, Jimmy Stewart sits down on the piano bench with Duke as he plays in a bar, and Stewart and the film’s creative team had to fight to keep the scene of a black man and a white man sitting together in the final cut of the film. The freedom and goodwill of the music aligned with the freedom from unjust social constraints. In a case of jazz and film cross-pollinating abroad, in the late 1950s the Frenchman Louis Malle was developing his debut dramatic film, Elevator to the Gallows. As a fan of the music of Miles Davis, Malle took advantage of Davis’s presence in France at the time to approach him about writing and performing the score. Malle established a truly collaborative partnership with Davis. The American became acquainted with the film’s story and then produced music organically that supported and accented the plot and characterization deftly. This artistic connection unmistakably contributed shortly thereafter to the approach and the craft of Miles’s 1959 LP Kind of Blue, the best-selling jazz album of all time.

Let’s go back to 1998 one more time (if only that were possible). That album by Sonny that I found was called Don’t Ask. It was recorded in 1979, and the key collaborator on this thing was a guitar player whom I’d never heard of before named Larry Coryell. I had grown up listening to the guitar pyrotechnics of my uncle Michael, but I would go on to learn that Coryell had played a key role in the path of this instrument, building on the seminal work of giants such as Les Paul, Charlie Christian, and Montgomery. In this pairing with Sonny, the track “Disco Monk” was one that I shared with anyone who would listen. People would listen and then simply stop and laugh as the piece’s radical shifts in tempo took them off-guard. The critics largely regarded it as a failure, but for me this track bridged the flamboyance of 70s dance music with the deep meditations in the monastery of melody and improvisation. I consider myself very grateful for whatever luck and synchronicity brought those two musicians and supporting cast together for that one-off recording.

Finding new and inspiring music is always great fun, but jazz has continually provided me with old and inspiring music that was new for its time. Last year I had this kind of experience when I came across the Vince Guaraldi Trio’s recording Jazz Impressions of Black Orpheus from 1962. Guaraldi had been inspired by the movie referenced in the title, and he was one of the early takers on Bossa Nova — but with limited interest at the time from record labels. This moment was before his iconic piano stylings would become the soundtrack for the Charlie Brown and Peanuts TV specials. Guaraldi used this album as a bridge from cinematic and rhythmic inspiration to an unexpected place as he found a spot on the pop music charts with his 3-minute single “Cast Your Fate to the Wind.” Other moments on that same recording foreshadow Guaraldi’s sound as Schroeder’s piano on the Peanuts specials — as good of an illustration as one could find of jazz’s essential position in American culture.

I know that the vast majority of people to whom I talk these days will never have heard of Sonny Rollins. That’s OK — we now live in times in which the canon is broader and more diverse and changeable than it ever was in 1960 or 1850, and music is not about checking boxes. It never was about that for Sonny, who turned 93 years old last September. Today, The main thing for me is that as Campbell said, I was caught by it. I found that same feeling of contented captivation in 2019 after we had just moved into the house on the street named for hope. I was building a rocket made of almost 2000 pieces, following the directions on every page. As I did so, my then 2-year-old daughter would steal a piece or use the spares to make something unpredictable of her own design. As we worked, or played, we listened to a 2018 disc called Flight by pianist James Francies from Houston, appropriately enough. The title track seemed to go well with the building of the spacecraft, and another one called “A N B,” gave me a feeling of floating in zero gravity. In this way, music has been the art with which I have lived the most, and across the globe, that is probably as close to universally true for folks as anything is.

So with that, if you hear the drums of Art Blakey, the reeds of Sonny Rollins, or the voice of Sarah Vaughn, and you enjoy some of those sounds, well — then that’s one of our connections.

C.S.